Stephen Bulger Gallery is pleased to present John Max “First and Last” featuring two exhibitions of photographic work by Canadian artist John Max (John Porchawka) (b. Montréal, Québec, 1936; d. Montréal, Québec, 2011): “John Max Shouts: Enough, No More, I Want”and “Strike up the Band!.”

John Max was born to parents of Ukrainian origin who arrived in Canada in the 1920s. He studied painting with Arthur Lismer and music at the McGill Conservatory of Music before discovering photography in the late 1950s through Lutz Dille, whose work, strongly influenced by Europeans such as Cartier-Bresson, André Kertész, and Robert Doisneau, brought the subjectivity of the photographer to the fore. Max discovered in this approach something that corresponded with his own vision of the human condition. From that point on, he devoted himself to photography. While self-taught, Max then completed his training with Guy Borremans and Nathan Lyons.

Throughout the 1960s, Max worked on assignments for various magazines and for the Still Photography Division of the National Film Board (NFB) of Canada. During this immensely productive decade, his work was widely disseminated, particularly in the many exhibitions and publications of the Division. Max also produced photographs for the Christian Pavilion at Expo 67. He represented Canada at the Fifth Biennial in Paris in 1967, and took part in “Four Montreal Photographers,” an exhibition organized and circulated by the National Gallery in 1968. An exhibition of 57 photographs entitled “And the Sun it Shone White All Night Long” toured Europe in 1969, sponsored by the Cultural Services of External Affairs Canada. Max's photographic vision reached its maturity with the “Open Passport - Passeport Infini” exhibition (a sequence of 161 black and white photographs culled from Max's archives, some dating as early as 1960), organized by the NFB's Still Photography Division and shown at The Photo Gallery in Ottawa in 1972. It traveled to multiple venues in Canada until 1976 and was printed as a photobook by the Toronto-based magazine IMPRESSIONS as its special issue No. 6 and 7 in late 1973.

Following the critical success of “Open Passport,” John Max was inducted into the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1974, and received a Senior Arts Grant from the Canada Council to travel to Japan. Max had long professed his interest in the country's culture and spirituality, and he remained in Japan between 1974 and 1979, long after his temporary visa expired. Despite his protestations and desire to remain, he was arrested by the Japanese authorities, and thousands of rolls of film put into storage. Those storage conditions rendered many unusable, but he eventually brought the remainder when he returned to Canada. Max returned to a Montréal that had changed radically. Over the intervening years his health and creativity declined. Although he remained a key influence on many, he was no longer at the forefront of the creative scene in Québec and became increasingly obscure. In 1997 the Stephen Bulger Gallery presented “Swallowing a Diamond,” for which Max designed a site-specific installation of work from previous series.

John Max’s exhibitions comprised sequences of images that, when seen together, create a dynamic and provocative presentation that combines the formal and narrative elements of individual photographs into a more holistic experience. This exhibition presents his first solo exhibition of a sequence: “John Max Shouts: Enough, No More, I Want” (1960); and his 1986 sequence “Strike up the Band!” (1986).

THE IMAGE BETWEEN

John Max’s sequences are about you.

They were produced in such a manner that they anticipated your participation, the way a writer toils for the benefit of an imagined reader, building suspense or pre-empting assumptions with plot twists. Each individual photo has a clear referent—this artist, that moment, such a scene, etc.—but together they are also about something else.

It is difficult to categorize John Max reliably, because what he did changed meaning over time. For some, he was a talented portraitist with a knack for raw authenticity and the decisive moment; for others he was depicting brooding inner landscapes according to an arcane system of allegory. The two bodies of work on display here should convince you that he was both, and yet more.

John Max Shouts: Enough, No More, I Want was his first solo exhibition. In 1960, he had been photographing the simmering arts scene of Duplessis-era Montréal for about five years. Embedded in his milieu, he followed night and day painters, engravers, sculptors, actors and writers, but also puppeteers, jewelers, textile artists, and muralists. In their workshop, on site installing pieces, on stage performing, or just hanging out, they were photographed by John Max’s Nikon S2 rangefinder without shame or complicated setups, but always conspicuously. The son of Ukrainian immigrants from Galicia, John Porchawka was a tall and bulky fellow who could not hide himself physically. Adopting a pseudonym and cultivating his secrets allowed him to keep the invisible part of himself concealed instead.

“John Max” had already been used a few times in group exhibitions and as byline in the press for his work, but in this first exhibition it was incarnated as an avant-garde artist persona. Helped by his friends, writer Jean-Claude Germain and architecture student Arnie Gelbart, Max organized this collection of portraits using tropes and methods laid out by Alfred Jarry, Dadaists, Antonin Artaud and anarchists, who all read the Gospels against their grain. Many people shown are important artists—among them Armand Vaillancourt, Robert Roussil, Jean-Paul Martino, Ghitta Caiserman, Guy Borremans, and Suzanne Rivest—but none are identified by their name. They are instead parodic equivalents of the Twelve Apostles, the Holy Saints, Christ’s Last Words, and Christ himself being crucified; equivalents thrown at the face of a Roman Catholic audience by a Greek Catholic photographer lapsing into atheism and theosophy.

Expectedly, scandal ensued, and the exhibition initially setup in the hall of the recently inaugurated McGill University’s McConnell Engineering Building quickly decamped to a Main-adjacent jazz club, Le Mas. It is debatable whether the protestations by the building’s titular benefactor were due to the presence of nudity or blasphemy, but they would be worn like a badge of honour by the artist.

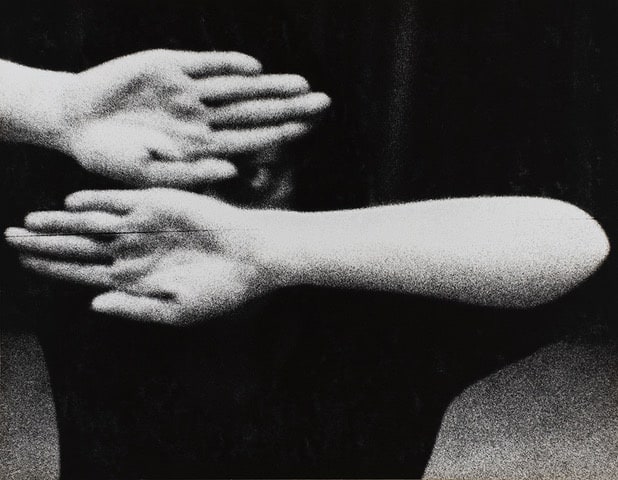

Provocation is mainly the juvenile part of John Max Shouts; its more lasting characteristics may be instead the emotional impact of the images and their implied drama. Selecting both decisive and undecided moments, printed with intense contrasts and careful cropping, John Max put together in this exhibition something other than a panorama of bohemia. Like a circus planting its tent amidst flatlands, he conjured up a make-believe world of wonder and cruelty. This should give us pause for a moment to recalibrate our usual historical scheme of a “subjective” or “fictional” turn eventually affecting “documentary” or “straight” photography by 1970. These practices have always been concurrent, and in 1898, Fred Holland Day had already re-enacted with his Boston friends the Seven Last Words of Christ.

Hence to 1986 in the blink of an eye, we Strike up the Band! that tolls the bell of John Max’s career—if defined by his printing and sequencing of new images. No scandal attended the exhibition when it opened, which drew in few people and a shrug of indifference from the critics. John Max had not changed his modus operandi that much, but the institution of photography in the 1980s was skeptical of the medium it had itself defined as a slice of reality. The subtle formal transitions, the smooth symbolic continuities between Max’s various portraits of friends and strangers, in Montréal and in Japan, did not have the jarring ironical bite upon the codes of depiction that was then de rigueur, nor did the sequence overtly address systems of knowledge and power. These were not literal portraits and travel photographs, but their symbolic dimension was glossed over.

In Max’s archive, I found a manuscript sheet giving the correspondence between the individuals and their role: Guy Borremans is the captain of the ship seen departing from a Japanese dock, garlanded with ribbons; John Schweitzer is the Joker holding forth in his gallery; the woodworking tool seller is using his notebook as a ledger for keeping track of entries into life, like the newborn child of the driver besides the old lady. None of this could be seen in the photos; only between them, and by paying careful attention to the titles. It was perhaps easier to see that the young girl opening the gate is looking at the band passing by, but pictorial storytelling is in our culture the province of comics, and in 1986, they were yet to be “not for kids anymore.”

Together, these two bodies of work create another, new sequence. Tracing a trajectory throughout photography in Canada during the twentieth century, they belong to a medium that speaks, in addition to showing. More than cut-outs from the real or from the imagined, these sequences articulate ethical statements, protesting in the major key against shame and self-hatred, and appreciating in the minor key the subtle trembling of life’s journey. This range of dynamics needs an attentive, but not an absolute ear. Finally, they are also spiritual, but more from their inquiry into life’s meaning than their occasional religious iconography.

John Max has long been narrowly considered through the small puncture into the fabric of his concealments that remains his major work Open Passport. These recovered sequences are two additional frames flashing, for you to see the image between.

–Michel Hardy-Vallée, 2022

Michel Hardy-Vallée, PhD, is a historian of photography and independent curator who has researched and written extensively on the work of John Max. Hardy-Vallèe is currently adapting his doctoral dissertation about John Max’s Open Passport into a monograph for an academic publisher, and he has advised on photographic prints acquisitions by museums and private collections. He was a guest curator at the 2022 Rencontres internationales de la photographie en Gaspésie. Hardy-Vallèe has written the following essay about the two exhibitions on display.